The Large Hadron Collider/ATLAS at CERN | by Image Editor

So now ONL18 is over and I can look back over it all and see what I think with a little distance. I can say that it was not a fun beginning for me, but two things kept me going. First, I know that part of my personality is to feel stress and frustration as soon as something is not easy for me (trust me, I have been working on this!). Second, the wonderful people in the group and facilitators grounded me; they seemed to take it all in flow and I tried to follow their lead.

The tough beginning did not last all that long, however. Once we got going with the topics, it seemed to all make sense and I started to feel like I was catching on. As documented in previous blogs, I came across many questions in the work I did with the group. And I came up with some answers. Now I am thinking about how I might use all that I have learned if I am going to adapt one of my traditional classroom courses into something more blended. At the most basic level, I know exactly what an online course looks like and feels like now. I could sit down and organize one right away because I just went through the experience of being in one. That is valuable! Putting it all together, I consider the following points to be the most important.

- Pay attention to variation in digital literacy

I learned tons of new great digital tools in this course, which means I am well prepared to design the physical infrastructure of the course. Care needs to be taken, however, not to throw too many new ones at students all at once and to provide support for those who will be doing something new by using the digital tools. Perhaps even offer a brief intro to digital literacy and create the perspective that this is something students will benefit from working on.

- Learn before arriving in the classroom

This is basically what the flipped classroom idea is all about, as promoted widely by Eric Mazur (perusall.com). To me, this is a teaching design principle that is absolutely essential if we expect students of heavy static content to engage in collaborative learning. Provided with good resources, students should be able to get a basic understanding of concepts and information that they can then put into practice with group exercises.

- Complexity matters!

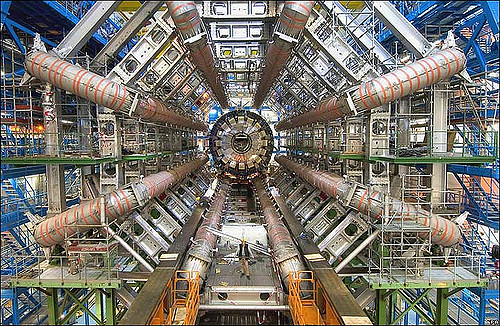

Problem-based learning (PBL) (Dolmans et al. 2005) is a brilliant and simple idea: embed learning in a contextualized and constructed problem for students to solve collaboratively. In this course, we were guided in the PBL method through the use of the FISH model. Honestly, I did not get the value of using the Fish model. It helped structure the work a bit in terms of what we talked about when in the course of the two weeks. But it also felt limiting, in the sense that we felt we should talk about what the focus could be for an entire session, what we should investigate during the next session, etc., instead of moving more quickly to putting together ideas when we could. Of course, it could be that other groups used the tool differently and it worked brilliantly. What I learned about collaborative work and learning is that the level of complexity should be rather high for it to bring benefits over that of working independently (Kirschner et al. 2009). This brings to mind a quote by Peter Higgs (hence the pic above of the Hadron Collider): “…it has become obvious that on the experimental side, there has been a huge evolution in the number of people who have to collaborate because of the gigantic size of the instruments used, but also because of the enormous task that is data analysis”. Okay, maybe it is a little grandiose to liken anything I am doing to the mind-blowing collaboration in the world of physics, but I do think pushing the frontiers of science increasingly requires collaboration of great minds. This is particularly the case if we are to transcend disciplinary boundaries and open up new research directions. My point here is that I don’t think the value of collaboration comes across unless the task is too much for one person to manage well or requires diversity of skills beyond what most of us have.

- Social integration

I had no idea social integration is of key importance to student retention in online courses before this course. But it makes sense. And I have no doubt that my growing connection to the people in my group made me show up to more meetings and try harder to fit in all the work I should do. As mentioned in a previous blog, I believe the teacher’s role in fostering social integration should be hidden. We have to trick students into it or else many serious, self-motivating students will balk at our efforts. Which brings me to my final point…

- Gamification of courses

What better way to lighten the atmosphere and get people interacting than to introduce a few well-designed and well-timed games? I think this also may have the effect of increasing students’ commitment to learning material, as most will want to do better. Being confronted in a fun way with the fact that you don’t know something may even increase the desire to pay attention. As Stefan Lagrosen wrote in his blog, gamification can “tickle the competitive spirit”. This blog also provided many leads on gamification tools out there. I particularly thought Nevin et al. (2013) was interesting. Check it out!

To wrap up what is turning out to be an unusually long blog, I should mention that I have the sense that university administrators perceive “going blended” as a way to free up classroom hours and, hence, cut costs. We did not get into this in our course, but I think I can say quite definitively that teaching online is not a way to cut hours. It could if care for quality was dropped: I could record a lecture once and use it year after year. But providing teaching, cognitive and social presence goes well beyond recorded lectures. There is much more to do in some ways to make sure the scaffolding and support are there for the students, especially if we don’t want retention affected.

References

Dolmans DJM, De Grave W, Wolfhagen IAP, Van der Vleuten CM. 2005. Problem-based learning: Future challenges for educational practice and research. Med Educ 39:732–741.

Kirschner, F., Paas, F., & Kirschner, P. (2009). A Cognitive Load Approach to Collaborative Learning: United Brains for Complex Tasks. Educational Psychology Review, 21(1): 31-42. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10648-008-9095-2

Nevin, C. R., Westfall, A. O., Rodriguez, J. M., Dempsey, D. M., Cherrington, A., Roy, B., Patel, M. & Willig, J. H. (2014), “Gamification as a tool for enhancing graduate medical education”, Postgrad Med J, Vol. 90 No. 685-93.

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Garrison, D. R. (2013). Teaching in blended learning environments: Creating and sustaining communities of inquiry. Edmonton: AU Press.